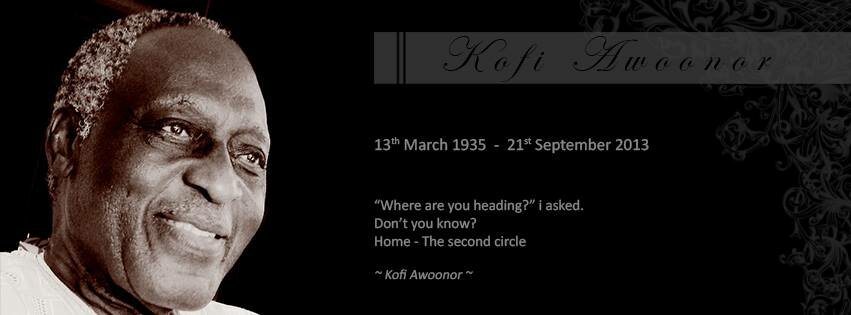

Although I am a new admirer of Kofi Awoonor and his poetry, I have been deeply saddened by the loss to the world that his tragic death has brought. From the small state of Rhode Island in the United States, I share the sadness of losing such a man.

It is ever more poignant that the loss of such a great man came while he was attending the Storymoja, a peaceful gathering to celebrate life and what literature can bring to it. The circumstances of Prof. Awoonor’s life and death make it ever more incumbent that we, here in the United States, there in Africa, everywhere and anywhere, devote our lives to the celebration of LIFE and the ending of hatred and violence.

Thank you, Kofi Awoonor for your life – it has made living so much more meaningful to all of us.

Sincerely and with deep sadness,

Jay Miller

Former Judge

Adjunct Professor of Law

Newport, R.I., U.S.A.

I am certain there are others who, like me, received invitations to the recent edition of the Storymoja/Hay Literature Festival in Nairobi, but could not attend. My absence was particularly regrettable, because I had planned to make up for my failure to turn up for the immediate prior edition. Participant or absentee however, this is one edition we shall not soon forget.

It was at least two days after the listing of Kofi Awoonor among the victims that I even recollected the fact that the Festival was ongoing at that very time. With that realization came another: that Kofi and I could have been splitting a bottle at that same watering hole in between events and at the end of each day. My feelings, I wish to state clearly, did not undergo any changes. Read the rest of the tribute and his promise here.

Thank you for organizing the tribute for Prof. Awoonor on Monday evening. As I struggle to make sense of the past few days’ happenings… I have put a few thoughts together as my humble tribute to Brother-Elder Prof. Awoonor and within this space; I am also remembering others that have lost theirlives or got injured in this so deeply violating and unfortunate incident here in Kenya.

I humbly request that you accommodate my “rogue” third main stanza of 40 lines (42 with spacing) – representing and dedicating 10 lines for each of the 4 days as we looked on painfully yet hopefully in anticipation to an end to the madness. Below is my tribute. Peace!

Ask No Questions Child

in memory of Brother-Elder Prof. Kofi Awoonor

ask no questions child

for elders know things…

laden with pregnant bindings

things that feel, smell, sound

like an Eagle’s thwarted soaring,

solemnly crumbling,

yet enfolded in arms

strong like pots

of the ancients,

smeared with jinxed herbs

for the healing

incantation

ask no questions child

for elders know things…

laden with pregnant bindings

things curved out of

optical-fibers, thorns, “surplus gunpowder”*

seeds, grains, roots, glass,

bark, rocks, thread, glue,

iron, ochre, hair strands, nucleic acid,

porridge, yam, sorghum, rubber,

copper-lime-spewing cotton

molds of cyanide,

laying cockroach eggs

for the hushed

feasts

of

doom

ask no questions child

for elders know things…

laden with pregnant bindings

things that elude us,

yet severely, gnaw our minds,

evoked in balance…

Wind, Sun, Water, Moon, Fire, Earth;

Àṣẹ! Àṣẹ! Àṣẹ! Àṣẹ! Àṣẹ! Àṣẹ! Àṣẹ! Àṣẹ!

a consecrate, plentiful basket;

we aspired…

to reap,

harvest together,

a festival!

“storymoja”*

but

…

ALAS!

…

ogres;

amanani,

majitu,

ebirecha,

mashetani,

emerged…

in full costume

from dungeons

alien-to-childhood-folklore…

swarming, swirling, swathing;

slimy, sluggish, slough

clogging, clinging, clanging,

fire–spitting tongues,

in sacred places …

hither and thither;

birthing,

a severely obscene

abhorrence,

with their saliva’s

malignant defecation,

poisoned

in

broad

daylight

(exhausted)

ask no questions child

for elders know things…

laden with pregnant bindings

things unfolding

a chocked, sliced moon, quadrupled

into hollow, senseless horrors,

snatching

souls,

young-old,

a beautiful rainbow of souls!

now ferried, yonder, before us…

to witness,

the dances of the ancestors;

relay our libation, receive!

quench the thirst, commune!

calm the rage

imbibed in shadows,

baffled in time,

a

desecration

of

systems

&

values…

atrociously

failed

ask no questions child

for elders know things…

laden with pregnant bindings

Ask

No Questions

Child?!

Says Who?

Mwalimu, Brother- Elder

Kofi Awoonor

Cultured Us…

to Ask Questions!

Indeed…

The “Canoe”* Has Arrived.

Paddle On… To the Other Side,

Brother-Elder Kofi Awoonor.

Worthy of Touching their Faces…

Dancing… with the Ancestors… Beyond Infinite, Golden Sunsets

May Peace Be Your Guide and Abode,

Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ…

Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ…

Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ…

Àṣẹ… Àṣẹ…

Àṣẹ…

“Look for a canoe* for me/That I go home in it/Look for it/The lagoon waters are in storm/And the hippos are roaring/But I will cross the river/And go beyond…”

…

“… I heard the voice of a gun/I came to have a look/Who are those?/Who are those saying/They have surplus gunpowder*/And so we cannot have peace?”

Prof. Kofi Awoonor from his poem “I Heard a Bird Cry”

Kerubo Abuya

Nairobi. 26th September 2013

There are few people that can make a first impression so lasting that it makes you see your craft in a whole new light.

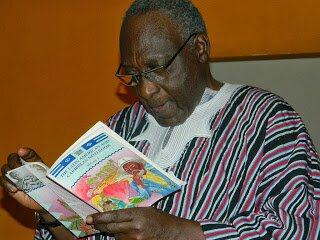

I first became aware of Prof. Kofi Awoonor when I heard that he was to speak and have a masterclass at the Storymoja Hay Festival. I became interested in his work after reading a study of his work, ‘This Earth, My Brother’.

His masterclass on ‘The Responsibility of the African Writer’ was especially revealing. Here was a man who had written longer than my country had been independent. He represented a link with the past, with the age-old traditions of singing and performing poetry that are now classified dryly as ‘Oral Literature’. The fact that these poems and songs of Africa have influenced genres as varied as spoken word, hip hop and rap show that African literature has a profound contribution to make to the rest of the world.

He was a man who found humour in everything, even in the fact that his name had been misspelt in the event programme.

He was also a man who loved language. He spoke 5 Ghanaian languages fluently, along with French, German and Dutch. Remarkably, at his age, he was also learning Portuguese to translate and promote his work in Portugal. He confessed that he counted himself incredibly lucky to have never been rejected by an editor. His dedication to his work, and the lengths that he was willing to go to were legendary.

One thing that he loved though was to read. In his opinion, the best way for a writer to build up his work was through reading the works of others. He started with the classics, with Jane Austen’s love affairs and James Joyce’s Ulysses. In the course of his reading, he encountered interesting, sometimes subtle themes. He pointed out that Shakespeare’s ‘The Tempest’, for example, contains an interesting narrative about colonization and language, where Caliban’s freedom and rule over the island is broken by Prospero’s sorcery. When Prospero lands on his island, Caliban treats him well, and Prospero in return teaches him a language with which he could express himself. The way the English language was imposed on Africa, however, led to an interesting side effect: we were able to talk to each other directly, providing a convenient point of exchange.

While African English is a colonial construct, its bonus is in giving us a way to communicate directly – Kofi Awoonor at #SMHayfest

— Mugendi Nyagah (@IAmMugendi) September 21, 2013

However, even when we talked to each other in English, we still remained in touch with the creativity that our languages possessed. Where direct translation failed, we often resort to imagery.

The quirks and comedy of African languages show up in translation. People 'hear' smells and 'drink' cigarettes – Kofi Awoonor at #SMHayfest

— Mugendi Nyagah (@IAmMugendi) September 21, 2013

Prof. Awoonor’s provocation to write was from a sense of obligation. One of his grandmothers was a priestess who performed incantations, while the other was a dirge singer. He felt that he needed to contribute to the culture of his people by promoting their poetry, both in the original language and translated to English. Another provocation to write that he shares with Chinua Achebe was the need to go against the prevailing opinion that Africa had no culture. Achebe had written ‘Things Fall Apart’ in response to ‘Mister Johnson’, a story of a bumbling African clerk that made so many mistakes that his life became a farcical representation of how the colonialists viewed Africa.

Ultimately, the heart of the masterclass was the fact that we all have an obligation to write as Africans. In order to do this, we need to answer four questions.

Before you write, ask yourself: Who am I? Where am I from? What is it I want to say? How do I want to say it? – Kofi Awoonor at #SMHayfest

— Mugendi Nyagah (@IAmMugendi) September 21, 2013

1. Who are you? Not just your name, but the sum total of your identity. If you don’t know who you are, then you are lost. You need to have confidence in yourself first before you write, and this arises from your understanding of what you are made of. One of the ways to answer this is to look at where you come from, the people who have gone before you. Everyone has ancestors with whom we share an inescapable link, and identifying these connections makes it easier to identify who we truly are.

2. Where do you call home? We all carry our homes around with us, like a snail with its shell. Home is where your art, your being and your true purpose lie. Home is part of identity. This is why the most eloquent stories that we can tell are those around us, those that contain in them the things that we are most familiar with.

Even for people who would consider themselves rootless, the people who live in cities like Nairobi who feel rootless also have a home that they can find and connect with.

Even 'rootless' urban Africans have a strong connection to tradition which is a deep source of inspiration – Kofi Awoonor at #SMHayfest

— Mugendi Nyagah (@IAmMugendi) September 21, 2013

3. What makes you think you can write? Until you can answer this question, anything you say will lack conviction. We all have stories that we can tell, but that alone is not reason enough to write. We should write because we have things that need to be said. He summed this up with a saying, ‘I have something to say, and I will say it before death comes. Let no one say it for me.’

4. What would you want to write about? He noted that there are many things that can be written about, ‘as many as the range of human emotions’. Every emotion is legitimate, and so it comes with its own story. Stories are a testament to the human condition, where conflict is engrained, and that is why we are happy when they are resolved. Good stories can also leave the situation hanging for the reader to resolve on their own. Every writer contends with his historical background and uses it as a source for his writing. We need to write more of our own stories, to share our perspectives as African writers with the world.

Stories are after all about meetings and partings, where we are introduced to the characters in the beginning, go through the story with them and say farewell at the end. How we feel towards them, how we feel towards the situations they are in, that is something that is brought out by how it is written.

His love for poetry showed in his lament for how it is taught. Taking the art of the poem and making it a dry, complicated matter was especially painful to him, starting with nursery rhymes. Poems are made to be performed, to be sung out loud and given the dignity they deserve. Poems, he said, are religious experiences that deserve to be treated with respect.

Poetry was meant to be read out loud, to be sung, to be performed. Take that away and all you have is dry words – Kofi Awoonor at #SMHayfest

— Mugendi Nyagah (@IAmMugendi) September 21, 2013

When writing, he suggested that first drafts should be used as a guide. He was always editing his work until right before he needed to send it to the publisher, and even after it had been published, he still found edits that he made and incorporated in various edits. He also dedicated himself to popularizing poetry, even though he knew, and acknowledged with a laugh, that there was no money in it. Poetry, according to him, was art for its own sake.

Professor Awoonor was a champion of African literature, and he will be sorely missed. To honour him, I suggest you read some of his work. And every time you write, be true to yourself.

‘This Earth, My Brother’ and more of his work are available on Amazon.

Farewell, gentle soul.

Nairobi. 25th September 2013

Kofi Awoonor,

killed on Saturday, September 21, 2013

at the Westgate Shopping Mall in Nairobi, Kenya

Terror had struck once again.

The insanity of rage, and the rage of insanity

continue to ransack and ravage,

blatantly, pointlessly,

striking out against the innocent,

victimizing without any sense or reason,

alleging causes for which there is no justice,

aimless bloodletting without end.

The perpetrators of this latest violence

very obviously did not care

who came into the sight of their guns…

they simply aimed and fired

at anything or anyone who moved,

snuffing out the light of lives

like candles flickering in the wind,

massacring, maiming, murdering

indiscriminately,

targeting the young, the old,

men, women, children…

all of whom had done nothing

to warrant these insane acts

of revenge and retribution,

for things done by others…

in other places, at other times…

One of the many

who had been brutally mowed down

by hails of bullets fired from assault rifles,

the great Ghanaian scholar-poet

Kofi Awonoor.

They killed a poet,

but they could not kill his poetry.

The silenced a man,

but they could not obliterate

or invalidate his messages,

the many words he had written and spoken

in a life time of service

of the scholarship, literature

and culture of his country.

A man of peace had been struck down and taken

from those who loved and admired him.

The actions of the terrorists merely proved

that they could strike at will

and in a reign of terror,

to instill fear in the hearts

and minds of the innocent.

However, they failed

to prove a point

or serve a purpose

of real substance or meaning,

other than creating chaos,

and causing acts of absolute horror…

death and destruction,

pain and suffering,

senseless, brutal, violent, vulgar,

and utterly insane!

They killed a poet,

But they could not kill

his poetry!

His words will endure.

Gerhard A. Fürst

USA. September 25, 2013

Dear friends,

I.

I wanted to say that the hearts and thoughts of both me and my wife are with each and every one of you now. And they will be for a long, long time. Together with you we share the grief, the anger and the unbearable sadness that washed over us following the devastating attack on Saturday. Together with you we share the earth shattering pain over the ones who were killed, the one who were injured, the ones who were trapped inside Westgate.

Together with you we mourn.

Even though we are now back in Oslo, in our hearts we are still together, following you on internet via updates on websites and social media, seeing pictures of you all from the deeply moving tribute you held to remember the late Kofi Awoonor.

You are not alone.

Neither of you.

The only ones alone are the terrorists who on Saturday thought they had the right to decide who should live and who should not. As if they were the extension of some God’s Hand. The ones who believed they had the right to inflict such harm on other people’s lives, the ones who, through their insane rhetorics, got the totally, utterly and completely fucked up idea that their lives and their cause was more important than the lives of everyone else who happened to stand in their way.

These are the only ones alone.

They will continue to be alone.

The rest of us will remain together, regardless of where we are staying and where we call home. This disaster is not just a Kenyan disaster, it is a global one, and so regardless of where we come from and what our religion may be we will all need to continue standing together, crying out for a world where conflicts are solved with words, not weapons.

II.

I would also like to take this opportunity to thank you all for how you handled the situation on Saturday, from the moment I met Lyndy after my last session with a small, wonderful audience of Kenyan teenagers and she told me “there’s been an incident” to her deeply comforting remark later on: “Don’t worry, we got you.”

There were other reassuring voices as well, from Jo, from Aleya and Moses. From other participants from Kenya and abroad, and festival personnel, all of which had a harder time than myself.

I cannot thank you enough for this.

Even in the time of crisis, under immense stress, you made sure we were ok.

You showed real courage that day when I had none.

I will always be grateful for that.

III.

Though our experience in Nairobi forever will be connected to the attack on Westgate, we will also remember, with joy and fondness, our stay and our experience prior to what happened. I was so proud to be invited to the Storymoja Hay Festival and I am so grateful for your friendliness, hospitality and how easily we all shared our love for literature and art. I cannot think of a friendlier people than the Kenyans. Neither will I forget the Masterclass session I had where I, together with so many promising Kenyan and African writers-to-be, had trouble controlling ourselves in our shared enthusiasm for the worldwide potential of African literature.

So these memories, from the festival and the time we spent together, the great nation of Kenya itself, the weirdly beautiful city of Nairobi (not to mention driving from the airport to the hotel as the sun was coming up and people were walking to work) and the out-of-this-world magnificent experience we had during our two days in the Rift Valley and up at Lake Nakuru will always stay with us. Hopefully, in time, these memories will also prove to be stronger than the ones we have from Saturday.

In my mind, there is no doubt: both the Storymoja Hay Festival, Nairobi and Kenya will push through this devastating tragedy and blossom like never before. And we will stay beside you, cheering you on, promoting Kenya, the festival and its writers and, once in a while, even push through our own anxiety and fear, just long enough so that even the cowardly lions among us will be able to say: “Don’t worry. We got you.”

I end this letter with two words from the end of Tony Kushner’s great play “Angels of America”, two simple little words who perhaps sum it all up, who should be the motto for the future:

More life.

All best,

Johan

NAIROBI, Kenya–I will travel to Ghana to be present at the burial ofKofi Awoonor. I will because he is a great Ghanaian poet. I will because he is a remarkable African thinker and mentor. I will because he traveled to Jamaica from Ghana to bury my father, his dear friend and mentor, in 1984. I will because he is my uncle, my mother’s cousin. Read the rest of this tribute to Kofi Awoonor by Kwame Dawes on Wall Street Journal

“Something has happened to me…

The things so great I cannot weep”

from “Songs of Sorrow” by Ghana’s Kofi Awoonor.

Something has happened. And we will write about it, we will write something beautiful. Something that will help those who are struck down with grief to keep hope alive. And we will celebrate those who have been taken from us. And we will continue to make the world more beautiful.

Kofi Awoonor was murdered by terrorists in Nairobi while attending the Storymoja Hay festival. And the festival was cut short this year. But it will come back. Again and again and again. And I will come back to it with stories, and with hope.

Because over four thousand children eagerly attended the festival during its three short days. Children who deserve to be inspired. Children who deserve to express themselves creatively and passionately as they grow. Children who deserve to dream and hope and laugh.

Those children deserve to be free from terror. We all do.

And they deserve to read as much as they want of the best of books that there are, to open their eyes and hearts to the whole wide world.

This is what Hay festivals worldwide are about. An opposite to terror. And they will continue, beautifully, hopefully, creatively.

In memory of Kofi Awoonor and all those who died this weekend.

“It goes on, this world, stupid and brutal.

But I do not.

I do not.”

from “Revolution” a novel for young adults by Jennifer Donnelly.

- Atinuke Akinyemi

It wasn’t evening

before the sun was missing.

It wasn’t dusk

but the sun was gone.

Who stole our source

of poetic food?

Who stole a muse

Who sad our mood?

Who made us drink our tears

in

sips

of

mourning

cheers?

Who

set

the

radiant

sun

before the come of dusk?

Aaaah…

Good upon the good

Evil upon the evil ones!

Adelaja Ridwan Olayiwola

Nigeria 23rd September 2013

You ask me what I see

I see green

That stretches and stretches

It embraces the pregnant blue

Held heavy with silver

Not a static one

But this silver hops and hops around

I’ll tell you what I see

The plains of that savannah

Where the cheetah cares not

For the king of the jungle

Though the hyena skips the rhinos

And the zebras zigzags the buffaloes

You ask me what I see

The plains where roses bloom

Through green houses

Tea and coffee compete

On the heights of Tigoni

I’ll tell you what I see

Though the valley been rifted

And flows lazily down

Through contours once chrisom

Now wails with blood

And wounded with fear

You ask me what I see

For those languid fools

Who trade god for sale

Take hate as company

And pair grenades as berries

Terror from the belly of ‘Shabaab

I’ll tell you what I see

Crumpled but not crushed

Bent but not broken

While not Uhuru

The shield and spear

With Harambee

Stands firm

Unbreakable and unbeatable

Nwachukwu Egbunike

Ibadan, September 23, 2013

Deeply shocked by the death of the Ghanese poet Kofi Awoonor I want to send you our condolences from Rotterdam where Mr Kofi Awoonor twice performed at the festival Poetry International, in 1981 and 1994. He then read the poem “at a refugee camp” that deeply touched me today again.

Anne Vegter

Rotterdam, September, the 23, 2013

I first came across George Awoonor-Williams when I read an interview with him by Francis Gass-Porso in the Accra Sunday Mirror of August 26, 1962. Asked, “Doesn’t the fact that the African writer has to publish his work abroad demand from him a false tone?” he replies, “The sooner we establish a high-powered publishing house, the better it will be for us.” I still have the press cutting. (Awoonor interview)

The first time I saw him in person was in December of the same year. He was playing the lead, Brother Jeroboam, in a Ghana Drama Studio production of Wole Soyinka’s The Trials of Brother Jero at the Commonwealth Hall Amphitheatre at the University of Ghana. Tickets cost two shillings, three shilling and five shillings. His performance left a lasting impression on me. I can still see him in his white robes on Lagos beach.

In 1964 I was working in India but still subscribing to Black Orpheus. Kofi’s long poem, I Heard a Bird Cry, was published in no. 15 of August of that year. (file attached) In it I read words which seem to have some relevance to the tragic events of yesterday and today.

Look for a canoe for me

That I go home in it

Look for it

The lagoon waters are in storm

And the hippos are roaring

But I will cross the river

And go beyond …

Who are those coming

With their heads covered with velvet?

May be they are moondwellers

Tell them, tell them that the dog

Does not bear a child in public

And the fowl-eating hyaena

Strikes only at night.

I heard the voice of a gun

I came to have a look

Who are those?

Who are those saying

They have surplus gunpowder

And so we cannot have peace?

My brother, go in peace.

Manu Herbstein

Accra

The BBC’s Rebecca Kesby spoke to one of Kofi Awoonor’s friends.

In his poem At the Gates, Kofi Awoonor wrote:

I do not know which god sent me,

to fall in the river

and fall in the fire.

These have failed.

I move into the gates

demanding which war it is;

Which war it is?

The Ghana Association of Writers has learnt with profound shock and sorrow the death of Professor Kofi Awoonor who has died tragically in the attack on the Westgate Shopping Mall in Nairobi, Kenya. It is sickening that Professor Awoonor and scores of other innocent people should die in an attack that is related to one of Africa’s longest and bloodiest political crises. By his death, Africa has lost a literary giant.

Professor Kofi Awoonor, who wrote seven books was a founding member of the Ghana Association of Writers and belonged to the generation of Independence-era writers whose literary output gave a voice to Africa’s developing nations and helped define their cultural identity and agenda. His influence on Ghanaian and African writing is apparent in the number of writers, especially poets that he empowered to apply their own authentic experiences to their work. It is no wonder that he was appointed at an early age to be the first director of the Ghana Film Industry Corporation which had been charged by the first President Dr. Kwame Nkrumah to harness the country’s creative resources for its literary and filmic heritage.

Professor Awoonor, lecturer and teacher of five decades, influenced thousands of students and in his later years returned to teaching in creative writing at the English Department of the University of Ghana. It is significant that Professor Awoonor died in the service of literature at the Storymoja Hay Festival of Literature and the Arts where African writing is nurtured and displayed.

The Ghana literary and creative arts community has lost a stalwart defender of culture, and to the Association his passing is an irreplaceable loss. At the last Congress at which he delivered the keynote address, he paid glowing tribute to his departed writer colleagues and remarked poignantly that he wished to be similarly remembered at his death.

The Association sends its condolences to the family of our departed friend, advisor and mentor. Our hearts go out to the bereaved families and we wish speedy recovery to those injured in this senseless and tragic act. We also express our solidarity with the Kenya nation and pray that it and the region will soon overcome this adversity.

As we remember Kofi Awoonor on this sad occasion, we recall his own words in which he described himself and his mission as a writer:

“I have gone through the trauma of growth, anger, love, and the innocence and nostalgia of my personal dreams. These are beyond me now. Not anger, or love, but the sensibility that shaped and saw them as communal acts of which I am only the articulator. Now I write out my renewed anguish about the crippling distresses of my country and my people, of death by guns, of death by disease and malnutrition, of the death of friends whose lives held so much promise, of the chicanery of politics and the men who indulge in them, of the misery of the poor in the midst of plenty.”

Kwasi Gyan-Apenteng

President

A precious one from us has gone.

A voice we love is still.

A place is vacant in our hearts

which no one else can fill.

After our lonely heartaches

and our silent tears,

We will always have beautiful memories

of the one we loved so dear.

Servant of God, well done!

Rest from thy love employ.

The battle is fought, the victory won.

Enter thy Master’s joy.

Prince Osei Tutu

What happened at the Westgate Mall in Nairobi on the 21 September 2013 is NOT the world that was imagined when the theme ‘Imagine the world’ was coined for the Story Moja Hay festival. None of us could imagine a world that within seconds could turn a harmless shopping spree into a nightmare of terror, blood, death and mayhem. Certainly not Prof Kofi Awoonor, poet and diplomat, who had come to Kenya to support and give his wisdom to the greatest of causes; the education of children and the wider community into the culture of reading and the acquirement of knowledge through books – Not when he and his son walked into the Westgate Mall on that tragic day to be confronted with an armed attack that resulted in his demise.

It is hard to accept, to imagine, that because of this heinous act we have lost such a great and powerful literary personality. This is a great loss, not just to the African continent, but to the whole literary world. His death is proof of the senselessness of such acts. Sadly in taking his life, those who did this also took away a part of their own heritage. Because what Prof Awoonor gave with his work was not exclusive to his homeland Ghana, nor to the African continent. It was and is a contribution to the enrichment of our world as a whole.

Let Prof Kofi Awoonor’s death not be in vain. Despite what has happened we cannot stop believing that we can imagine a world that will one day achieve a level of global literary exposure that will bring us closer together instead of tearing us apart. We must not!

May his soul rest in peace.

Auma Obama

On my twitter I tweeted that I will blog about my SMHF experience this week, and I had intended to do it so in the manner which the events I attended happened, but the passing of Prof. Kofi Awoonor in the Westgate Attack prompts me to make a tribute for/ to him, and to share what I learnt in his master writing class dubbed “The Responsibility of the African Writer”.

Prof. Dr. Kofi Awoonor was a Ghanaian diplomat, a teacher and a politician during different periods of his life, and was a poet until the time of his untimely death. He studied in the University of London, and he worked for the late Kwame Nkrumah in the years 1962-1964. He had six children, among whom one is a girl. He had seven grandchildren, among whom one is a boy. He was friends to the late Dennis Brutus, the late Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. He wrote two novels: This earth My Brother and Comes the Voyage at Last, a book which has been translated to German, Dutch, French and Italian. His mentor was the father of Kwame Does whose master writing class I also attended, (and who I will also blog about as the week progresses.)

A man of easy charisma and welcoming manner (he allowed me to take photos of him and even posed for me), he imparted a lot of writing wisdom on all who attended his class in a simple clear manner. He was generous with his experience lessons; answering all the questions that we threw his way and he also read us some of his poems on request.

I would like to share with you all he taught us who attended his writing class on Friday 20thSeptember 2013, but I will limit this post to the four questions he posed to us. All writers should stop and ask themselves these questions.

Who are you as a writer?

This question constitutes these other questions: What is your identity. Where were you born? What are your roots? What have you grown up to be?

Where do you call home?

is where your heart is, he said, but most importantly ask yourself; Where shall you call home?

What makes you think you can write?

The ability to write something meaningful should be built from self-confidence, and the belief that you have something meaningful to say.

What would you like to write about?

A thing to remember while writing is that life is a series of parting and meetings, he remarked. He said that partings make him sad, and that death is one of life partings. He reminded that as writers we should develop the sense that death is inevitable and every emotion is legitimate. We should not be afraid of writing the reality of both.

Apart from the four questions posed, he said that the most essential part of writing a short story is conflict- a fundamental part of human existence.

***

My friends and I were grieved to learn of his death, and the news that his son also sustained injuries from the Westgate attack.

If you can, pay him your last respect. Join others at a gathering that will be held at the National Museum on Monday, September 23, 2013 from 6:00pmto 9:00pm. It has been organised by the Story Moja Hay Festival organizers.

To all those affected by the Westgate terrorist attack directly, I offer my sincerest condolences. To all the Kenyans shaken as much as I am, or maybe more: we are One in this. Things will be alright.

Rest in peace Prof Dr. Kofi Awoonor.

To a man of faith death is a bridge,

A small bridge connecting mortality to immortality,

To a man of faith death is a gate,

A small gate ushering men into their eternal home,

To a man of faith death is a pool,

A small pool where sweat and tears of life are wiped,

To a man of faith death is victory,

A big victory after a purposeful living in ones days,

To a man of faith death opens a new page,

A blank page whose footnote and header are God’s Spirit,

To a man of faith death is just but a dot,

A small dot within the long story of God’s eternal living,

To a man of faith death is a key,

A key connecting one with a long desired life of joy,

To a man of faith death is a welcome visitor,

A welcome visitor after a fully assured life across it,

To a man of faith death is departure from a room,

Departure from a changing room in hope to appear on His stage,

To a man of faith death is like sleeping on the coach,

Sleeping on the coach to later wake up in the arms of Christ,

Indeed to a man of faith physical death is nothing to grieve,

Nothing to grieve but victorious rest.

Fatigued and shaken we wait

The smell of death spreading

Caught up in a war of another

The news have nothing new

Imaginary screams of babies

Calls for mama, daddy and god

In a second their eyes meet

His stare fearfully triumphant

Sounds of helicopters

And the loudness of fear

In the sirens of our hearts

I weep for me. You and all.

Tears for unknown friends

and familiar strangers.

The deaths I have died.

Mine and others’. We die.

Your ancestors and mine.

The coffee has been cold

A sun and a moon after

The cups sit uncollected

He was here just yesterday

Kofi Awoonor has crossed over

In the shadow of our deaths Kofi

We carry life with grace

And when the shadow dies

We are dead to our own deaths

We have died before

Deaths not our own

And with one death

We offer to you a sacrifice

And in the death of another

We have had our slice

In the death of the everyday

We have become dead to life.

And in our dead lives

We can no longer live

As though we weren’t dead

To our own lives

But when our deaths come

We will have forgotten how to

And our tears will be for another

We have been here before

Too much pain mate

But not enough synonyms

Streaming thoughts of hate

And possible antonyms

Still I love

I am Death; the reaper of the harvest

that ye have sowed.

Ye, who my peons are; my subjects faithful.

But barren would my fields remain

and my plantation wither

without your ever-loyal tithe;

the robot that ye owe me.

***

I am Death; the minder of your duties

that ye towards your ruler bear

my loy’l vice gerent. Prostrate before him

in the same gentle dust

that soaked so faithfully

your brethren’s and your sistren’s blood

before. And will drink so again. Ever and ever.

My yoke is harsh; but light I make your conscience

and where my weight unbearable

appears to you, and you to throw it off conspire;

I gently take away

your memory;

for mild I am as much as cruel.

***

I am Death; the scarer of the crows

the terror of the peace

disturber of your beauty.

Oblige ye must me – in word as well as image

as Gitahi now has done; my loy’l, beloved serf.

I slay and spare

as is my sov’reign whimsy.

At times it even is the beautiful and innocent

crawling out of the vent duct, where she hid;

the caterpillar that I shall

into a butterfly create

or simply squash with those my boots

My boots that christened me as kimendero

my garment proud, which Isaiah exalted

adorned with noble purple

spilled from the cups of blood ye duly offer me.

***

I am Death; equating without equity.

At times I spare the hideous and the guilty

and give them all the honours that I took from ye.

Your Lords who now shall no more leave ye

to lands abroad and misty and policed

where justice, my old fremeny, would terrribly await them

but whom I now have given licence

to enslave ye forth; as ye desire and deserve.

***

I am Death, the equalizer called;

but some before me are more equal,

and called by me more commonly

into my court.

None of ye all be safe;

the oldish bard is not, and not the feeble infant

whom mother dearly clutched – only in order to deliver it to me.

For all of ye I love; although not equally.

***

I am Death. I rule ye

and yet upon ye I depend

because I cannot reap what ye did not

faithfully sow before

what ye did not

with bloody water feed

and fertilize with words

so thousandfold before.

Bowing before ye deep, I thank ye well

for service that ye loyally rendered.

Now ye bow in turn, and give me obeissance.

And weep your tears; because they are the flood

that I demand twice every year

to fertilize my cotton-rich and grain-decked fields

with water drawn

from all your Africa.

-Alexander Eichener

You sleep on your hand Kofi, laid

Silent in a coffee splash on Nairobi’s floor

By mumbling devils.

How rudely has your dance of cocoa and coffee tastes

Been interrupted, at this moment turned into a

Morning of your blood!

We cannot bear our leadened hearts, shame

Weighing us down that your god finger has been folded

By sissies here under our greening sun.

Would you Kofi understand

Any fingers that splattered men’s blood & coffee

Like does a hen scratching asunder bush faeces?

Neither would we.

Your finger must be unfolded somehow, and a life

Communed in this coffee and cocoa tango.

A scorching Tero Buru shall therefore thunder I foresee,

And our choice bulls will stampede from here to Accra:

Awoonor take this to the Ewe bank,

Not a single Mogadisho bush will withstand the trampling hooves,

Or grow hardy enough to hide the fingers of scarecrows.

No, this will be no revenge, not a coward’s bile:

A Passover.

Your spilled blood smeared on our foreheads,

And your poems tattooed on our tongues

Will deliver us to life atriumphed, and we shall ride

Your monument home atop our bulls’ longest horns!

Then we will sip silently,

And nod in cocoa and coffee bliss

Erohamano, Migosi Kofi Awoonor.

OLUOCH-MADIANG’ Kisumu, September, 2013.